Big data will save us all. Or so some technical pundits reckon. Before I go into that a brief excursion into history is required.

In 1979 there was an accident at a Three Mile Island nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania. The engineers had unwittingly let some water leak into the wrong system which triggered a shutdown of the main pumps responsible for cooling the plant. Sadly, the pipes feeding the backup pumps were incorrectly shut after maintenance. Normally the techs would have been warned, but the warning light on the control panel was hidden by a paper tag. The situation quickly spiraled out of control and the engineers trying to work out what was going on had to deal with an operating panel with over 759 lights, switches, and alarms. They had plenty of indicators that something was very very wrong but no idea on what to act on first. The situation was eventually resolved when a new shift started in the control room discovered and a subsequent inquiry resulted in the redesign of instrument panels for nuclear plants.

This is a great example of how knowing what’s important is very different to having a lot of information.

It also highlights some of the risks associated with the Utopian vision of big data and how there will be a new wave of technology innovation from the transformation of big data into big insights.

The big data hype is a few years old and has been characterised as the dawn of a new age of enquiry and the end of theory. Chris Anderson famously wrote in Wired that:

This is a world where massive amounts of data and applied mathematics replace every other tool that might be brought to bear. Out with every theory of human behavior, from linguistics to sociology. Forget taxonomy, ontology, and psychology. Who knows why people do what they do? The point is they do it, and we can track and measure it with unprecedented fidelity. With enough data, the numbers speak for themselves.

Anderson reckons that with enough data, models and the scientific method become irrelevant. What’s important are “statistical algorithms [that] find patterns…science cannot.”.

The promise is the end of speculative theory and the dawning of a glorious new age of facts and THE TRUTH embodied in the 2.5 quintillion bytes of data collected every day.

Anderson’s Utopian vision grossly oversimplifies the process of human enquiry which is rather than being continuous is based on disruption, discontinuity, rupture, threshold, limit, series, and transformation. Also his theory about the end of theory does not take into account that data is selected, segmented, and stored in a cultural framework, a system of references or contexts which inform and a informed by an idea that the datum has some intrinsic value.

Nothing happens in a vacuum and there is no magical data fairy pregnant with the truth waiting for a statistical blip to reveal herself and give birth to meaning.

Simply put, analysis, knowledge, and ideas don’t work in that nice, neat way.

The PRISM data collection program revealed by Edward Snowden and The Guardian remind us that big data is also insidious and frightening. According to Snowden, the US Government collects all kinds of data and metadata from email, video and voice chat, video, photo, voice-over-IP chat, file transfers, and social networking details. The objective is to “keep Americans safe” according to one US Senator. The most insidious part of this kind of big data is that businesses can, totally without my permission, collect information about me and my activities, and sell it to the highest bidder. Whether the outcome is an incredibly relevant advertisement for a new hair shampoo, or a police warrant for offences as yet unknown is beside the point.

As a citizen of a modern democracy I am entitled to my liberty (to use an old fashioned word), and my privacy. The government that monitors and interferes in my private activity without my permission has breached the trust which makes me pay my taxes, drive the speed limit, and generally do the right thing. Similarly, as a consumer I am entitled to hide my compulsive and habitual donut purchases from my health insurer.

I can’t help wondering what insights are gleaned from this apparently massive sophisticated and extensive data collection exercise. For example, if all my online activity has been monitored, is the analysis good enough to predict what I am go into say next?

Unlikely, but it could be useful. I wouldn’t mind knowing myself.

It’s not all doom and gloom. There is a positive aspect to big data which while not being an all-seeing magical truth fairy, promises to assist both businesses and individuals make better decisions through better insights. The data is important, but the presentation, transformation, and analysis of the data is essential for there to be the possibility of any insight. New types of businesses are focusing on the transformation and presentation of data to provide insight and value to customers – Klipfolio, Skift, GoodData, Datameer, BlueKai, Gnip, and DashFolio (from Flippa).

Big data, big insights, and big privacy are going to be three key trends in the next 100 years. Businesses that invest in data insights will grow and businesses that don’t will decline. Some businesses will differentiate by saying they don’t data-mine or share data with third parties and be able to charge a premium for the privilege of privacy, and other businesses will differentiate by becoming incredibly efficient with big data – Wall Mart is a great example of this.

Just as the promise of big data has within it the hidden threat of surveillance, that same threat represents an opportunity for businesses to build safe-rooms for individuals to insulate their lives against the prying eyes of government and industry, and to provide insights about who and what are doing the prying.

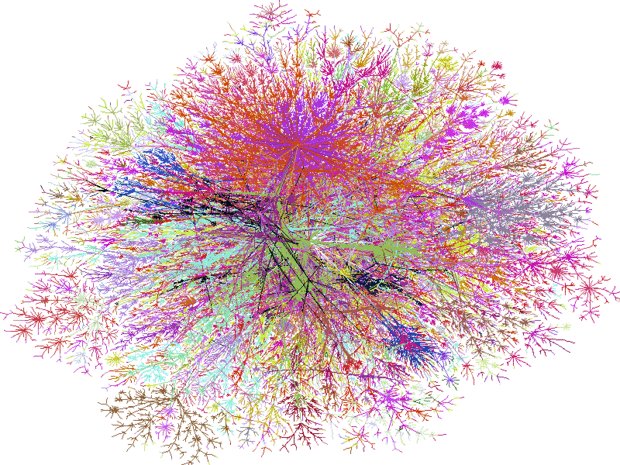

Image Credit: Jurvetson