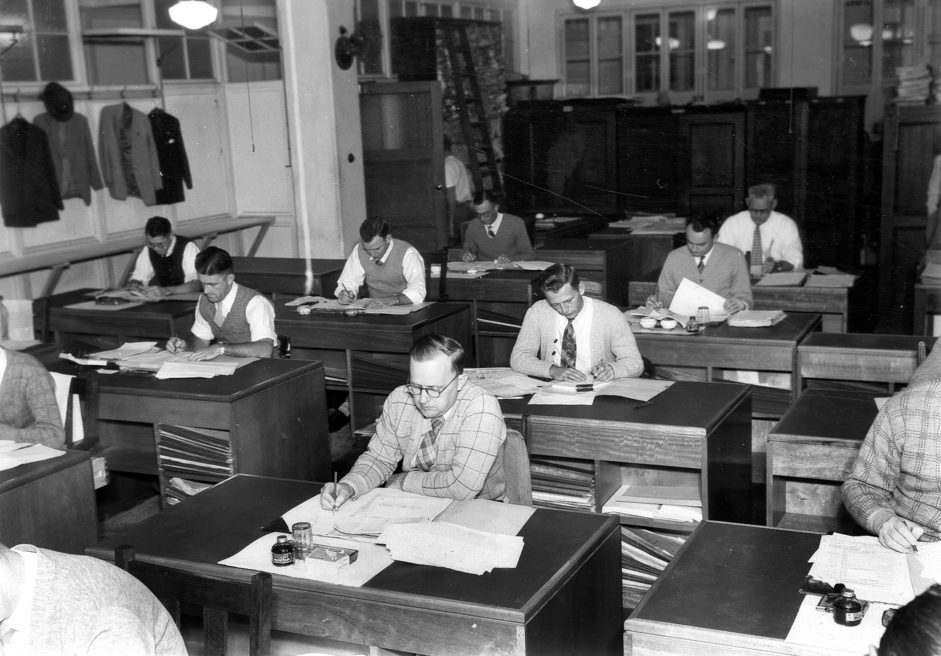

When I started my working career in an engineering business, I worked in the office, with no exceptions. The working day started at 8:30 am in the office and finished anytime after 5.30 pm, often later. Technology limitations meant that calls, invoices, meetings, and customer support all happened from a building filled with co-workers (hopefully) working together to achieve a common objective.

Before I could afford to buy a car or motorbike I got public transport – the 96 tram from St. Kilda and a train to Footscray station which was exploding with $2 shops and heroin. At work, bikini calendars from suppliers lined the lunch room walls, and the culture was tough, industrial; the boilermakers and engineers didn’t talk much about empathy or bringing your authentic self to work. Australia was recovering from a deep recession and no one had heard of hybrid working.

Later, after changing careers to become a web development manager, I moved to the beautiful Melbourne hills and enjoyed a 65-minute commute to an office in Melbourne’s central business district. Working from home was now a thing. If a co-worker had to be dialled in to a meeting because they were at home, it was prefaced by eye-rolling, and a derisive “working from home are they”. Staff engagement surveys were important and people spoke about building an inclusive culture, but it was pretty clear that the culture happened in the office, not at home.

The commute was brutal. I once saw a man almost get into a fight because a fellow commuter had sneezed on a crowded train, without covering his face. By the end of the week, I felt like one of TS Elliot’s hollow men.

We are the hollow men

The Hollow Men by T.S. Eliot

We are the stuffed men

By 2019 I was a hybrid worker without knowing I was a hybrid worker. The startup I worked for was based in another city so I spent 3 days in the office and 2 days struggling with Australia’s poor broadband in my home office. Cloud technologies like Google Workspace, Slack, screen sharing, and the Atlassian suite made the process seamless. Still, there was a sense that it wasn’t really working unless I was in the office.

Then COVID-19 happened.

I started working for an amazing e-commerce platform based in San Diego with a team distributed across Russia. As I was the only person in Australia and people were freaking out about a pandemic, working from the office was not an option. So like many privileged workers across the globe, I became a remote worker. People bought their authentic selves to work via Zoom calls and Slack.

Shit still got done, but not everyone was comfortable. Some employers installed tracking software to make sure that staff were ‘really working’. Others insisted that Zoom be on all the time to make sure teams could collaborate, and some others insisted people come to the office despite health rulings. Commercial property lobby groups in Australia’s central business districts started to implore businesses to send their people back to the office for purely altruistic reasons of course. People started to speak about water cooler moments.

It all made me think about Michel Foucault’s Crime & Punishment, where he wrote:

“A stupid despot may constrain his slaves with iron chains; but a true politician binds them even more strongly by the chain of their own ideas… on the soft fibers of the brain is founded the unshakable base of the soundest of Empires.”

Michel Foucault, Crime & Punishment

Lately, with the pandemic crisis supposedly over and a global recession looming, the work happens only muttering has been getting louder. In late May, Elon Musk sent an email to Tesla staff making his thoughts on working from home very clear.

“Anyone who wishes to do remote work must be in the office for a minimum (and I mean minimum) of 40 hours per week or depart Tesla. This is less than we ask of factory workers.”

When asked if the report was genuine, he responded on Twitter.

Musk would be an interesting boss, although I suspect he doesn’t care much about bringing your authentic self to work.

Australian entrepreneur and media antagonist, Adam Schwab wrote an article for the Australian Financial Review correlating poor mental health with working from home and accused work from home fans of being “task fillers” and:

“people who are content in their role but don’t want to create or show initiative. It robs ambitious, younger team members of the opportunity to grow”

Adam Schwab, “Love working from home? Maybe you’re a ‘task filler’”, Australian Financial Review ($)

Putting cynical efforts by commercial property owners and anxious distrusting employees aside, the debate misses two important things. Firstly, workers are people, yes, actual human beings, and that culture doesn’t just happen at the office or in Zoom, or on Slack.

“[C]ulture consists of the values, beliefs, systems of language, communication, and practices that people share in common and that can be used to define them as a collective.”

https://www.thoughtco.com/culture-definition-4135409

It shouldn’t need to be said, but culture happens even when the boss isn’t listening.

A culture that is concerned with people will have systems and practices that support those people in the best way possible. These could be purely remote work, hybrid work, or Musk-style office work. If the systems and practices are not set up to support the right model, the approach will fail.

A culture without trust will not be able to thrive with remote work.

A business dependent on email communication will fail in a remote work environment.

A creative culture may struggle to achieve amazing results even with the best communication tools.

Getting the right working environment takes work, not polemics. It takes listening and acting, not paternalistic control.

We certainly have some challenges ahead of us. We are stepping into a hyrid model and seeing how it works first hand!